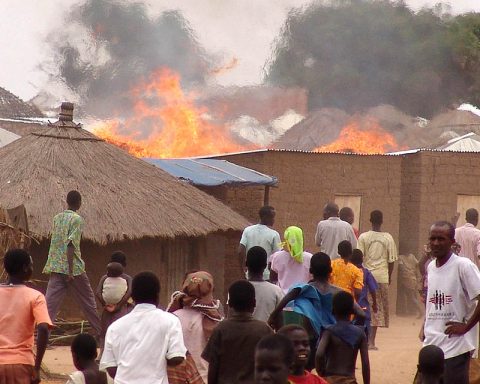

The bloody Saturday picture was extensively published between September–October 1937 and, in less than a month, had reached an audience of more than 136 million viewers. It displays a crying Chinese baby sitting within the bombed-out ruins of Shanghai’s south railway station.

The photograph soon became known as proof and evidence of the atrocities committed by the Japanese in China. It was captured just a few minutes after the Japanese had conducted an air strike on the unarmed Chinese civilians during the battle of Shanghai; photographer H.S. Wong was not quick enough to find out more about the crying child whose mother was lying dead close by.

An Eyemo newsreel camera took a photograph. It was named the Motherless Chinese baby and soon became one of the most memorable war photographs ever published. Harold Isaac, a journalist, mentioned that the photograph was one of the most successful propaganda pieces of all time as it brought about an outflow of western anger against the Japanese violence in China.

During the Second Sino-War, in the battle for Shanghai, the Japanese military forces marched and attacked China’s most populous city Shanghai. Wong, the photographer, mentioned he was on the rooftop of a street from where he rushed down and drove quickly to the railway station. It was a terrible sight; bodies were scattered all over due to the assault strike. He saw a man pick up a baby from the tracks and carry him to the platform. He returned to get another badly injured child whose mother lay dead on the rail tracks.

He quickly captured the horrific events, which he took the following day to the office of the Chinese press, where he showed enlargements to Malcolm Rosholt, saying, “Look at this one!”.

The morning newspapers reported that over 1,800 civilians, mostly women and children, suffered casualties at the hands of the Imperial Japanese military aviators while waiting at the railway station. The photograph was immediately denied by the Japanese nationalists arguing that it was made up and immediately put a bounty of $50,000, equivalent to present-day $900,000, on the head of photographer Wong.

At the war’s end, the Chinese media mentioned the total number of military and civilian casualties as at least 35 million, as the western analysts. They gave a figure of at least 20 million deaths.